This is the short answer: because positive reinforcement is a humane, science-based method of training animals that focuses on rewarding desirable behaviours. It is safe for everyone to use and it strengthens the bond between you and your animal.

- It is humane and safe because it does not involve punishment (be it verbal or physical). Animals have different levels of sensitivity and even though many dogs tolerate punishment, for others it may be a trigger to bark, bite or hide, ultimately escalating the situation instead of solving the problem. Therefore, using punishment is not safe. Secondly, punishment damages the bond between you and your animal, teaching the animal that they cannot trust you or even should fear you. (I also think that punishment is plain wrong and useless but it’s a matter for a different post).

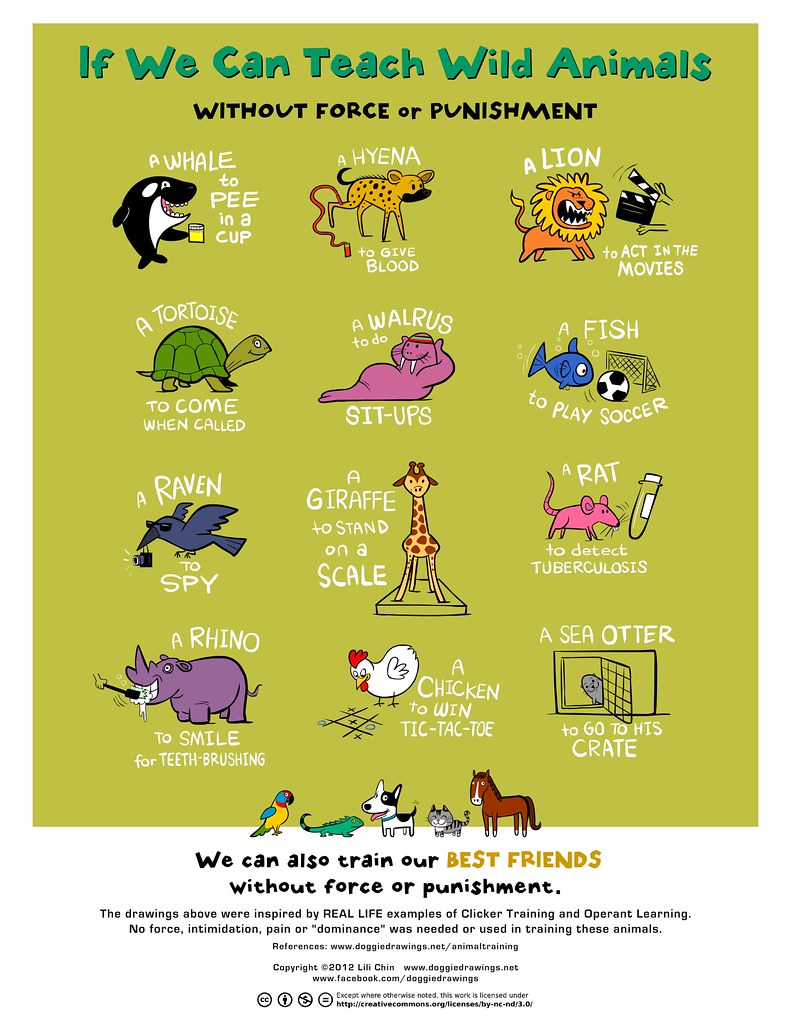

- It is science-based because it mostly uses the principles of classical conditioning and operant conditioning that have been well documented over the last hundred years. There has also been research into positive reinforcement itself that showed that animals trained by this method learned faster and retained the new skills much longer than classically trained animals.

- It is a method because once you learn the principles you can yourself train your animal. Of course what you train them to do and how long it will take depends on many factors (the animal’s age, experiences and predispositions, your skills, the amount of time you’re willing to invest…) but you definitely do not need to be a ‘dog whisperer’ to use it to your advantage.

Positive reinforcement…

- is not a quick fix. Like all successful training methods positive reinforcement requires us to think about our goals, plan ahead and manage the animal’s environment so that we can set them up for success. Most problems consist of multiple “bad behaviours” and each of them has to be fixed individually. (For example problematic greeting behaviour may involve barking, lunging and uncontrolled running. All separate issues for training.).

- does not mean that you have to use treats (or any other kind of reward) all the time. Yes, initially you treat each time. But once a behaviour is stable (reliable) you can gradually wean the animal off treats and only reward them from time to time. Unless it’s something that is really hard for them. Speaking of which, why are we so opposed to rewarding our dogs? No one ever asks when they can stop punishing their dogs… Without delving deep I’d like to make an argument for treating our dogs lavishly: most of the things we ask them to do are contrary to their instincts and obeying all our requests is hard work. In my opinion hard work deserves pay. Full stop.

- does not equal permissiveness. The difference between positive reinforcement based training and “traditional” training is how we react to the unwanted behaviours. Where a

ctraditional trainer might opt for correction1/punishment, the positive trainer opts for telling the dog what they want (instead of what they do not want)2because really, just expecting them to “know better” is plain unfair. Example: your dog wanders off the sidewalk. Instead of yelling/jerking the leash, one way would be to teach your dog the cue “sidewalk” and reward them for getting back onto the sidewalk.

- Not everything can (or must) be trained.